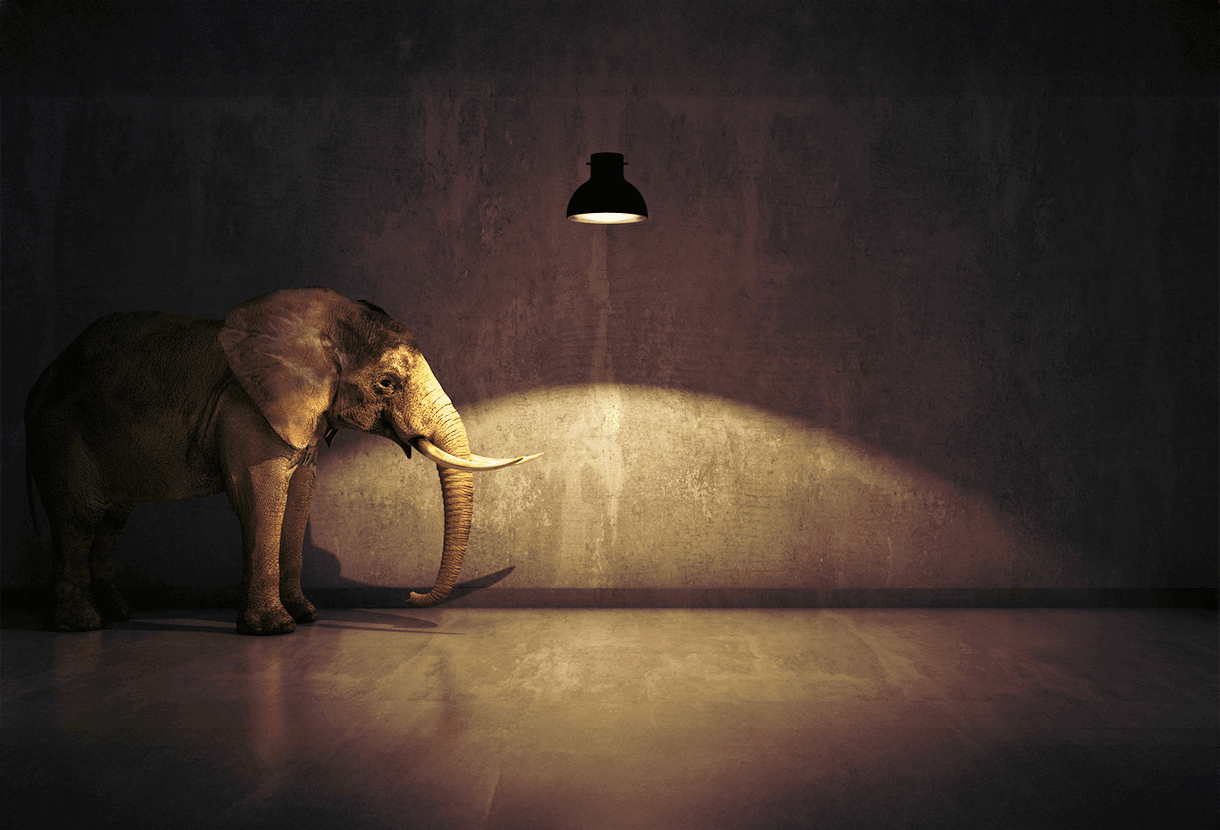

To address poverty, the federal government must first deal with the budgetary elephant in the room

November’s federal budget will set the tone for if and how the Carney government will address poverty in Canada.

In the short term, the government has made it clear that is has other immediate priorities that will make it impossible to invest significantly this year in income supports – the most effective tool we have for poverty reduction.

The longer path on which we are headed, however, remains blocked by a huge elephant in the room: defence spending. There is still time to deal with it, but unless something changes, recent spikes in poverty, homelessness, and food insecurity may be just the start.

How we got here

Before we turn to the future, let’s get a few things straight about the present.

In 1976, Canada committed under international law to “realize progressively” the right to an adequate standard of living, which includes rights to food, clothing, and housing. Progressive realization recognizes that these rights can’t be fully achieved overnight. Instead, governments should take steps over time – using all available resources and appropriate means – to make these rights a reality for everyone.

Despite this commitment, the past few years have seen more Canadians find themselves farther away from accessing the necessities of a dignified life.

The latest national data shows that Canada’s poverty rate is above pre-pandemic levels and is increasing among almost every demographic group and in nearly every province and territory. Rates of food insecurity are also rising, and the latest point-in-time count data suggests homelessness has doubled and unsheltered homelessness has quadrupled since 2018.

To be clear, we are not seeing these trends because everyone’s fortunes have worsened. With high-income households making more from investment income, and low-income households experiencing real wage stagnation, the data shows the incomes and wealth of the top 20 per cent are rising much faster than they are for everyone else. In fact, in the first quarter of 2025, income inequality reached another record high, beating the previous record set last year.

The good news is the government appears poised to respond to Canada’s desperately short supply of affordable housing through a new agency: Build Canada Homes. The details are still hazy, but we may be on the cusp of a generational investment in deeply affordable and supportive housing that will begin to build us out of decades of inaction.

As Maytree has argued, the government should maximize this opportunity by embedding a human rights-based approach in the new agency, retaining ownership of the newly built homes, and beginning with ambitious development on military lands that would contribute to Canada’s NATO targets.

Still, rebuilding our affordable housing stock will take years, if not decades, and those living in poverty, food insecurity, and homelessness deserve better today. Unfortunately, Canada is not on a trajectory to meet the Trudeau-era target to cut the 2015 poverty rate in half by 2030. The government’s own National Advisory Council on Poverty has said as much.

Staring the elephant in the eye

If there is one area in which the government has gone all-in, it is defence spending. On top of already planned increases, the Prime Minister announced in June that Canada will spend a further $9 billion on defence this year as a downpayment on reaching the new NATO target of 3.5 per cent of GDP spent on core military capabilities by 2035. (I am setting aside the overall 5 per cent target as it is unclear if this non-core spending can be achieved by reprofiling existing expenses as defence-related.)

What does the 3.5 per cent target mean in practical terms? In 2024, Canada’s GDP was about $3 trillion, and we spent 1.37 per cent of that on defence. Raising this to 3.5 per cent would have required $64 billion more, give or take a few billion. By 2035, the delta from 2024 is projected to grow to $118 billion annually.

It is difficult to comprehend just how large an investment this is. For comparison, consider that the most recent Public Accounts covering fiscal year 2023-24 show Canada’s total corporate tax revenue was $82 billion, total spending on Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement for seniors was $75 billion, and the combined value of the Canada Health Transfer and Canada Social Transfer was $68 billion. The Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates the government could increase the value of the Canada Disability Benefit to bridge the gap between social assistance and the poverty line at a cost of just $3.4 billion this year, growing to $6.2 billion in 2029-30. That’s pocket change by comparison.

This is not meant as a comment on whether Canada is right or wrong to invest in its defence. Indeed, Maytree believes we can leverage defence spending to pursue other social and economic goals, such as boosting housing supply. It is, however, meant to point out the mathematical reality that spending 3.5 per cent of GDP on defence will require the government to find a whole lot more money, and there are only two places it can look: new revenues or cuts to spending in other areas.

Things aren’t looking good on the revenue side. For now, the Prime Minister is ruling out higher taxes to pay for defence spending. Worse still, the cancelling of plans to raise the capital gains inclusion rate will cost $20 billion over five years that would have come overwhelmingly from the very wealthiest. Similarly, the government’s “middle-class tax cut” is projected to benefit almost no one living in poverty and almost all tax filers in the top income bracket. The price tag there is another $27 billion over five years.

If revenue is off the table, we are left with cuts. It is absolutely the case that the size of the public service has grown dramatically in recent years and may need rebalancing. It is also worth re-evaluating our spending priorities on a regular basis with an eye to achieving the greatest impact with the resources available. A proper spending review, however, requires fresh thinking – often from outside of individual departments that are not set up to consider how upstream interventions can reduce downstream costs. It also calls for a longer planning horizon that recognizes the time it takes to do the work of government differently, and that sometimes a short-term investment is required to unlock long-term savings. If this governments wants to be seen as smart implementers, it starts with a smart approach to spending reviews.

The current approach of across-the-board cuts of $25 billion over the next three years will almost certainly mean harming marginalized groups that rely on public services and programs. Moreover, there are powerful voices calling for even deeper cuts. For example, a recent CD Howe paper estimates that savings of $50 billion are needed to restore the federal budget to a “prudent path” and calls for the operational spending review to be extended to include programs provided through the tax system, many of which support low-income Canadians.

The choice is clear: raise revenues

Assuming the government is serious about maintaining sustainable budget deficits, something must give. It is our hope that the government opts to offset new defence spending by raising significant new revenues from the portfolios of the wealthy.

Without this shift, there is no path to meeting Canada’s poverty targets, and the government will be forced to significantly scale back the human-centred investments and social programs that deliver long-term, inclusive growth and prosperity. Bullets and bombs are not an excuse for ignoring hunger and homelessness.

The math is clear. The coming defence investment, and how the government chooses to pay for it, will likely be the Prime Minister’s defining legacy. There is an elephant in the room, and November’s budget will signal whether and how the government plans to address it.